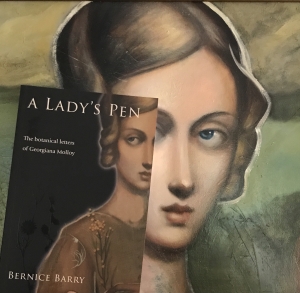

‘A Lady’s Pen’ The botanical letters of Georgiana Molloy

Writing a book based on years of research can take… quite a while. The publishing process, marketing and promotion eat up a lot of time too. When a new book comes out it’s an enriching but challenging time, an affirming but pressurising time, a joyful but fearful time. Most of all, it’s a time when there is no time for thinking about much else. Now, at last, I find myself with a quiet day at my desk on a gentle day that feels like an early end to winter. There’s a feeling in the air of new things ahead, and even though I still have a couple of small projects to complete, I can start imagining what might come next. Having time — thinking time — is surely the greatest writerly luxury of all.

But there’s a breathing space for reflection, too, so I’m looking back to answer questions I’ve been asked about the genesis of A Lady’s Pen. (University of Western Australia Publishing April 2023) Why did I first publish a full biography that didn’t focus on the scientific work for which Georgiana Molloy is remembered? Why did it take me eight more years to write in detail about her botany?

This book is probably the one I should I have written first in ‘the best of all possible worlds’ but I’m quite sure I couldn’t have done so before I’d spent all those hours getting to know the person, the time, the setting, the history and the other players on that stage. Our backgrounds, childhoods and early years have such influence on who we become that they shape us in ways we may not even be aware of. Discovering the details of Molloy’s family story and filling in what had been blank spaces in her first twenty-four years, gave me insights into her character that were invaluable in all the later research and writing. That understanding of what she’d been through even helped with the tricky business of transcribing her words. But most of all, I needed the time (make that ‘years’) to learn a lot more about the scientific world she was transported into when she began making her first collection around Taalinup (Augusta) in 1837.

It was a world dominated in nearly every respect by men. The settlers were under British law, written by men with no thought about how the same laws might or might not be administered in a place as different and distant as the West Australian bush, and in a community where the social norms that arrived on the Emily Taylor were disappearing within months as people adapted to a very different existence which included near starvation. Molloy was learning from Noongar people the names that had been assigned to local plants generations earlier, many of them unknown to the botanical world of Britain and Europe. As a woman born in 1805, the people she thought of as the experts were men and they’d never seen what she saw within a few metres of her home. Noongar women took her into the bush to show her particular flowers that were new to her. She realised these did not appear in the gardening magazines and catalogues she was reading. They were natural treasures and she knew more about them than the eminent men in London who gave lectures on botany. It’s unsurprising that Molloy took up the request to become a collector and devoted any spare time she had to that work with such energy and dedication.

I can see now that I’ve learned in much the same way that she did, as an amateur with a strong sense of intention and motivation, through research and investigation, trial and error. Most new understanding came gradually, over years, with the help of generous and knowledgeable experts but the biggest thing I’ve learned is that I still know very little about botany.

I recognise, now, that this isn’t a second book about Georgiana Molloy. It’s the story of a place and its biodiversity, the plants that are still evidence of uniqueness, the physical outcomes of being a living organism in the ecosystem of the ‘species rich’ Southwest Australian Floristic Region (SWAFR).[i] The Mind That Shines was a book about a person. The main characters in A Lady’s Pen are the plants.

An engaging fictional narrative usually reveals how the protagonist changes and that often holds true in non-fiction too. The plants’ stories are told through Molloy’s relationship with them, the interaction between the woman and the flora that shared the same environment for a short time. Each acted on the other; change happened. She was changed because of her ‘prevailing passion’.[ii] The indigenous species she collected (whether dried specimens or seeds) had their own stories altered too, but they became agents of change themselves, around the world.

In comparison with what some professionals gathered and sent to Britain, her collections were very small. She didn’t pack multiple bags of the same seeds in order to sell them. Her aim was to provide a matching set of viable seeds for each dried specimen, in the hope that growers and botanists would, one day, be able to see the living plant for themselves. Her field notes, written from a viewpoint not only scientific but also emotive, were different to those of other collectors. She tried to capture in words something more than the plant’s appearance. Those short texts reveal her respect for the plants in the most subtle of ways. Her own experience had long been shaped by living with adversity and it seems to me that the specimens she collected and prepared so meticulously carried with them not only the story of each plant and the environment that created it but also the part she had played — another species whose connection happened through an accident of fate, an unexpected request from a stranger.

When Molloy arrived on the banks of the Blackwood river in 1830 and endured the death of her first child after twelve days, she abruptly stopped writing in her diary. Weeks later, she opened the little book once again and wrote half a dozen words in pencil, the tentative beginning of a future. Those words were probably the first written record of Wadandi Noongar vocabulary in the Taalinup area. She could not have imagined that a few years later, she would be responsible for the first formal, botanical identification of Marri in Britain. Corymbia calophylla (formerly Eucalyptus calophylla) is one of the most common native trees in the Capes region and plays an important role in Noongar culture. We’re so familiar with the creamy presence of its lush flowers and the loud, drone of the bees that swarm to its sweet nectar, that it’s not easy to imagine a time when plant lovers in other parts of the world had never seen a living tree.

‘I was surprised during my illness to receive a nosegay from a native who was aware of my floral passion.’ [iii]

The list of species that I know she collected between 1837 and 1843 has continued to grow even in the weeks since publication of A Lady’s Pen. It includes specimens which have been lost since they were first documented so any evidence that she found them growing near her home has disappeared apart from a brief mention in a language I don’t read, in an old book. Others were destroyed in a fire. Some were once listed but are not extant today. A few, still retaining hints of the petal colour they showed on the day she picked them in 1839, can be traced back through the letters and diary entries of others to reveal the exact day they were collected and the place. One still holds its story from collection as a seed, through the dates of its ocean journey, to its new life as a seedling in a London greenhouse and then a full-blown flower, seen for the first time ever by British gardeners, then painted and published in a book.[iv]

Molloy had no concept of having arrived in a biodiversity hotspot but she did recognise (particularly after relocating further north to her new home, ‘Fairlawn’, at Yunderup/Undalup) the unusually wide range of native plants growing in the area. She worked obsessively to try and include every species, often struggling to identify small differences between one variety and another but she knew that was important, scientifically. The plants she collected in a wide range of habitats in the southwest between 1837 and 1842, include some which are now rare. The dried specimens are studied today by scientists learning more about the flora of this old, climatically buffered, infertile landscape where species are still being identified each year.[v] They are sometimes assigned new names as science learns more about plant genetics, each two-word phrase designed to tell its own story of derivation or botanical structure in a way that’s consistent worldwide allowing even more detailed study and comparison. There is still so much more to discover.

We must acknowledge that Molloy’s interaction with the native plants around her was more invasive than admiration, observation, name-giving or even domestic gathering for pleasure. She took flowers and seeds and sent them out of their environment, effectively ending the lives of each one but, in doing so, she gave enduring life to their stories.

[i] S D Hopper and P Gioia, The Southwest Australian Floristic Region: Evolution and Conservation of a Global Hot Spot of Biodiversity November 2004 Annual Review of Ecology Evolution and Systematics 35(1):623-65

[ii] Letter from Georgiana Molloy to James Mangles, January 1840

[iii] Letter from Georgiana Molloy To James Mangles, June 1840

[iv] Bernice Barry ‘A Lady’s Pen’ p. xxii

[v] S D Hopper, 2009, ‘OCBIL theory: towards an integrated understanding of the evolution, ecology and conservation of biodiversity on old, climatically buffered, infertile landscapes’, Plant and Soil, vol. 322, no. 1/2, pp. 49-86.